Unraveling the Mystery of Juvenile Batten Disease (CLN3)

While the umbrella term “Batten disease” encompasses over a dozen genetic disorders, the most common form that families and clinicians encounter is Type 3, known as Juvenile Batten Disease (CLN3). This specific variant presents a uniquely cruel timeline, often beginning with an everyday problem—failing eyesight—in a seemingly healthy school-aged child, before insidiously progressing to a devastating, multi-system neurodegenerative illness. Understanding the distinct pathway of CLN3 is absolutely critical for diagnosis, anticipatory guidance, and providing the compassionate, stage-appropriate care that these children and their families deserve.

Unlike the more rapid infantile forms, JNCL is a slow-motion tragedy that unfolds over one to two decades. It allows for periods of relative stability, but always with the looming knowledge of the progressive losses to come. This guide offers a deep dive into the specific clinical journey of CLN3, from the subtle first signs to the complex challenges of advanced disease, aiming to empower families with knowledge and provide a roadmap for navigating the difficult years ahead. It is a journey that highlights the critical need for early diagnosis and a proactive, multidisciplinary approach to managing complex diseases.

The First Domino: Progressive Vision Loss as the Hallmark Symptom

The clinical story of virtually every child with Juvenile Batten Disease begins in the ophthalmologist’s office. Between the ages of 5 and 10, a child will begin to experience subtle but persistent difficulties with their sight. They may struggle to see the board at school, become clumsy in dimly lit rooms, or have difficulty tracking objects. Initially, this is often mistaken for a common refractive error, but prescription glasses provide no benefit, and the vision continues to worsen. This is the paramount red flag for JNCL.

This characteristic progressive vision loss is caused by the degeneration of the retina, in a pattern that closely mimics a more common condition called retinitis pigmentosa. As the photoreceptor cells die off due to the toxic accumulation of lipofuscins, the child’s visual field narrows and their central vision deteriorates, leading to legal blindness by the mid-teenage years and, eventually, total blindness. An astute eye doctor who recognizes that the retinal changes are disproportionate to the child’s age or family history is often the key to unlocking the diagnostic puzzle and initiating a neurological workup.

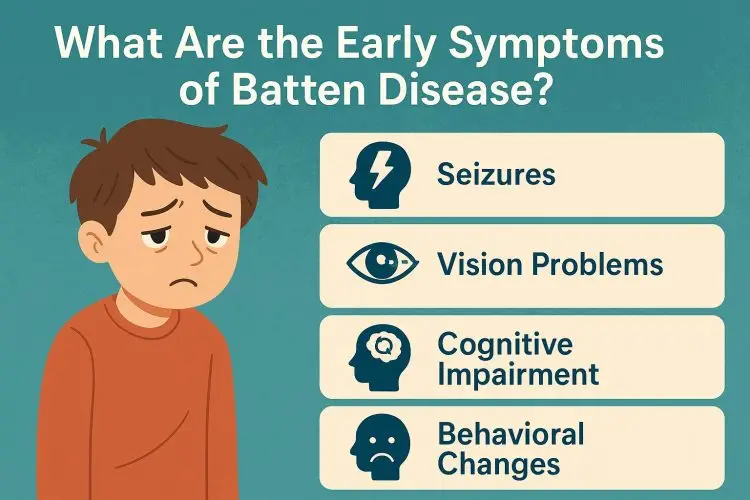

Beyond the Eyes: The Onset of Neurological Decline

For several years, vision loss may be the only significant symptom. However, typically in the early-to-mid teenage years, the second phase of the disease begins as the neurodegeneration spreads within the brain. The first neurological sign is often the onset of seizures. These can be generalized tonic-clonic seizures, but subtle myoclonic jerks and absence seizures are also common. Effective seizure management in teens with CLN3 becomes a primary focus, often requiring a complex regimen of anti-epileptic drugs.

At the same time, families will begin to notice a marked change in cognitive function. The teenager may struggle with short-term memory, abstract thought, and processing speed. This cognitive decline is not a learning disability but a true loss of previously acquired intellectual function, a form of childhood dementia. This phase is incredibly difficult, as the teenager is often aware of their own decline, leading to frustration, anxiety, and depression.

Navigating the Advanced Stages: A Multifaceted Challenge

As the individual enters their late teens and early twenties, the disease progresses to its most challenging stage, marked by significant physical and behavioral changes. A prominent feature is the development of parkinsonian movement disorders. This includes tremors, muscle rigidity (stiffness), bradykinesia (slowness of movement), and a shuffling gait, which ultimately leads to the loss of mobility and dependence on a wheelchair.

Furthermore, psychiatric and behavioral issues can become very pronounced. These are not willful acts but direct results of the deterioration of the brain’s frontal lobes. Symptoms can include apathy, impulsivity, emotional outbursts, and obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Managing these symptoms requires a compassionate approach and often involves medication alongside behavioral strategies, highlighting the need for a comprehensive understanding of the CLN3 gene‘s devastating impact.

The Cornerstone of Care: A Multidisciplinary and Palliative Approach

There is no cure for Juvenile Batten Disease. Therefore, the entire focus of care is on managing symptoms, preserving dignity, and maximizing quality of life. This necessitates a robust multidisciplinary care team that can address the patient’s evolving needs. The team must include a neurologist, physical therapist, speech pathologist (for eventual swallowing issues), and, crucially, a palliative care specialist.

Palliative care should be introduced early to help manage symptoms and to facilitate difficult but essential conversations about future care goals. The aim is to ensure the patient is comfortable, supported, and able to experience joy and connection throughout their life. Families looking for reliable information can turn to dedicated health portals like medicationsdrugs.com to better understand the full spectrum of care required for Batten Disease.

References

Comprehensive information on Batten Disease, its types, and management strategies can be found at leading medical information websites. For a detailed overview, consult sources like the Batten Disease Support and Research Association (BDSRA) and other authoritative health portals.